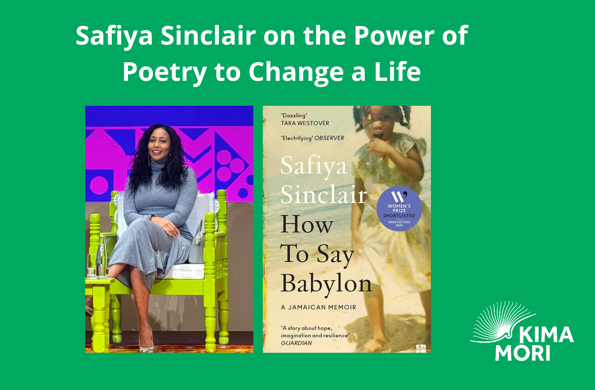

The Jamaican author discusses her memoir How to Say Babylon, the long claw of patriarchy and the magics of her homeland

February 28, 2025

When I was a teenager, I lived for a while with my older sister. A revolution and years of war had hurled us away from our birthland, far from our parents. She was in her early 20s, living communally with some musicians. One of them was a Rastaman from Martinique. Lithe, gentle and easygoing, he used to refer to his longtime girlfriend as his everything. “Jah” was often invoked, spliffs moved freely, evenings turned into impromptu jam sessions: djembes brought to the center, someone pulsating the shekere. In those days, Bob Marley and the Wailers, Burning Spear, Israel Vibration and The Gladiators formed the background music to our lives. Lines from Bob Marley (“Movement of Jah people!”) and The Gladiator’s songs (“Dreadlocks, the time is now! Stand up, fight for your rights!”) played like refrains in my head. I had a visceral understanding of the sentiments invoked but only a superficial grasp of its cultural tenor and political undertone.

This is to say that reading How to Say Babylon, the world conjured by Safiya Sinclair felt at once vaguely familiar and wholly unknown. Sinclair’s memoir sets out to challenge misconceptions about Rastafarians: that Rasta equates Jamaican, that a Rastaman is naturally a pure soul, that his home must be good-vibes-only territory. She lays out a brief history of the Rastafari movement, its birth in Jamaica as a response to British colonialism, her parents’ pull towards it and what their choice meant for her as a child and young adult. Most of all, Sinclair’s book is a coming-of-age story tracing what she herself rose against, emerging out of the patriarchal order that kept her confined and charting her way in the world as a woman and a poet.

How to Say Babylon follows Sinclair’s two poetry collections, and it is distinctly a poet’s memoir. In her gorgeous prose, dreadlocks turn into “live wires”, on stage they are thrown upward in the air like “a lightning bolt.” Hair pulled off the scalp becomes “stray tufts fallen to the ground, sad as dead animals.” Months stretch like “chewing gum between my fingers, sticky and flimsy.”

The storyline and the characters brought to life are remarkable enough but it’s the author’s care at the sentence level, the way she makes each line sing, her writing into the symbolism and lacing every image with meaning that sets this memoir apart. A dried-out caterpillar held in a jar is a being that lost the chance to free itself. Birds stand in for paternal affection but also fury. The seaside is maternal territory, the region where Sinclair’s mother hails from, but the sea, sea breeze and salt air, also reflect the instinctual knowingness that “there was nothing broken the sea couldn’t fix.”

I met with Sinclair earlier this month when she visited Dubai for the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature. We spoke about patriarchy, poetry as power, finding one’s voice, the weightlessness of forgiveness, and the lush magic of her homeland.

Ladane Nasseri: I want to start with the title of your book, How to Say Babylon, which also appears in the prologue. I have my reading of it, but what did the title mean to you?

Safiya Sinclair: The concept of Babylon is an important one for the Rastafari movement. It represents everything they are ideologically opposed to, everything they see as destructive or oppressive or “downpressive” as they would say to the Rasta bredren and the Rasta family. Everything that’s connected to colonialism, slavery, Western ideology, they see as Babylon. When the Rasta movement began in the early 1930s, they faced a lot of struggle and tribulation. They were attacked by the government, made to be outsiders by their families, they couldn't have jobs. They couldn't walk along the beach [fronts] because they were developed for tourists. All that pushed them inward. They became very secluded and saw anything connected to authoritarianism or the government as Babylon. In my household this idea of Babylon shaped our daily lives when I was growing up. It shaped the way my father viewed the world and the way he imparted lessons to me and my siblings about the world. He became increasingly obsessed with this idea of Babylon and its temptation being a corruptive force for us, particularly to his daughters. In some sense, he believed that the women in in the family were more susceptible to temptation. Every day, the main lesson was fortifying my mind and my body against the temptation of Babylon. So the book is tracing this sort of life, the education I got about Babylon and what it means —what it means when you say it, what it means for our family and what it eventually came to mean for me as a young woman trying to figure out for myself what path I wanted to take and eventually coming to a point where I saw my father look at me and see Babylon [in me].

Ladane Nasseri: What was your understanding of Babylon when you were a kid compared to now, having left Jamaica, studied in the US—the South specifically—and witnessed the expansiveness of systems of oppression designed to control certain bodies?

Safiya Sinclair: I recall my father talking about this as early as when I was four years old and to a four-year-old these grand ideas about the world being evil or oppressive, don't quite make sense. Babylon represented this kind of unseen boogeyman that was connected to the British monarchy and Western ideology and capitalism and all these things. When I was a young girl, I understood the concept, but I didn't know what the stakes were for me. In high school when my teachers were discriminatory to me, I had a better understanding of what my father was talking about, but it wasn’t until I got to the US that I could see up close the sort of wounds of racism, of discrimination on a systemic level, especially as a black woman walking through a lot of these spaces and having to interrogate that violent history. In Jamaica, even though we were under slavery and colonial rule, we were emancipated and in our town squares, our statues are of the slaves who led rebellions. Those are our heroes, right? So, when I got to the US and their statues were of the enslavers it’s as if I had to rewire my brain. What was really shocking was that no one questioned it, like ‘well, it's history! These are statues of enslavers and that's just how it is!’ Coming to terms with that history I had a deeper understanding of what my father meant when he warned of the evils of Babylon. I saw it for the first time, in a very tangible way.

"I wanted to choose for myself the woman I wanted to be and not the woman he was trying to shape me into. I was always looking toward a sense of freedom, of liberation. The freedom to just be. That's why I connected so much with literature and with writing, because it was the first space where I felt that sense of being completely free to nurture a self, to nurture a voice ."

Ladane Nasseri: In your book you tell the story of one family, in a country and a subculture, but your story has elements that are universal. I think of my own connection to Iran where I lived for a while under a patriarchal government. So, this diktat on hair, and the insistence on policing women's body, felt familiar to me. Did you think as you were writing that your story might find echoes in other countries, cultures, or religions?

Safiya Sinclair: I can't say that sitting at my computer I thought about that, but it was my hope that when I finished the book it would reach any reader, particularly women and girls who grew up in similar ways. Patriarchy is invasive. It's like a long claw that has held women for so long. Now that the book is out of, I've met many women from so many different parts of the world who have shared with me how closely they see themselves in the story. Women who grew up Mormon, or Christian, or Muslim, all in fundamentalist spaces. That has been probably the most gratifying. I feel grateful that any woman could look into my life and see herself.

Ladane Nasseri: Yes, that’s a beautiful thing. Talking about cultures and communities, certain countries or communities are misunderstood and as result easily vilified. As a journalist I’m always wary of playing into tropes. In your book, there’s a scene when your brother wants to discourage you from seeking outside help and says it's “family business.” Did you have any concerns that the abuse scenes could be read by some as another indication that people from certain backgrounds are inherently violent?

Safiya Sinclair: I don't see it that way. It's what happened to me and so, I did not want to censor myself. I wanted to be true to what happened and be as nuanced in presenting my father who did these pretty monstrous things. It was also so I could find some kind of opening to understanding him as a person and as a man, which is more than he did for me when I was that age. So, I was never going to look away from the truth of what happened, but I was very careful in trying to present him as a complex person who has his own wounds and whose ideas of the world and whose manifestations of anger and violence are also connected to traumatic post-colonial remnants in our country. A lot of people from that time are still coming to terms with the lingering effects of that post-colonial trauma.

Ladane Nasseri: That certainly comes across. When you were a young girl, you got a scholarship and you write, “I went one way and the other girl, the girl, I never became once the other.” Many times, you will yourself to take another path than the most likely one. What was leading young Safiya? What was she reaching for?

Safiya Sinclair: For a long time, I just wanted to not feel like I was suffocating under the tempestuous whims of my father. That’s what shaped my days and the way I thought about what I wanted my future to be. I wanted to choose for myself the woman I wanted to be and not the woman he was trying to shape me into. I was always looking toward a sense of freedom, of liberation. The freedom to just be. That's why I connected so much with literature and with writing, because it was the first space where I felt that sense of being completely free to nurture a self, to nurture a voice and be myself on the page. That became an opening toward imagining what could come next. And then, realizing that not only am I not going to be silent, but that I have something to say, and that perhaps what I have to say has power.

Ladane Nasseri: And that all came through words…

Safiya Sinclair: Yes, through seeing what words could do. There was a transformational feeling that came when I first began writing. I realized that so much of what I was feeling, whether it was hurt or pain or frustration or this idea of voicelessness…could be transformed into something else through writing. So, I followed that headfirst, wherever it was going to take me.

Ladane Nasseri: You have said that you see poetry as a very primal mode of expression. Do you think every person has the capacity to touch poetry, if not write poetry?

Safiya Sinclair: I do think every person has the capacity to touch poetry and be touched by poetry! That's what I do as a teacher, I try to be an ambassador for poetry. A lot of people overthink it. They think ‘I can't understand this’, or ‘it's something I need to analyze or take apart’ and I'm always saying no, release yourself from all of that. Just let the poem move through you. It could be a feeling, an image, a sound, a sort of music, a lyrical movement. If there's something you come away with from the poem that stays with you then that's all it needed to be. It’s the same when you look at art: what do you get from standing in front of this work of art? You let it move through you. So yes, I think everybody has the capacity to be touched by poetry. Absolutely!

Ladane Nasseri: What do you know now about yourself or about your relationship with your parents that you did not know before you started writing this book?

Ladane Nasseri: One of your mentors suggested that you write this memoir from a place of safety. How did you know you were finally ready to write it?

Safiya Sinclair: When I first began, everything was still happening. I was in the thick of it and I don't think you can write a memoir that way. I'm a very emotionally sensitive person, so for me it was still too fresh. I always say that's the best advice I ever got, to write it from a place of safety. One, because I didn’t know if I was actually going to survive the writing of it, how I would be on the other side of this if I wrote it. And two, it wouldn’t be the book I wanted to write because I had all these unresolved feelings. I was not in a place of safety in any sense of the word.

Then I did a poetry reading in Jamaica after being away for a long time and asked my father to come hear me read. ‘I just want you to hear me,’ I said on the stage. I was very nervous. I didn't know if he was going to. Afterward, he said, ‘I'm listening, and I hear you,’ and I thought, well, this is new, this is different what is this feeling? And I just felt that so much was lifted from me. Everything that had been sitting very burdensome on my chest, I felt it lift, and I thought, okay, I think I have it now, this place of safety. I think I'm ready to begin.

Ladane Nasseri: You dedicated your book to your sisters, your niece, and “she who is yet to come.” As writers we often write with an ideal reader in mind, sometimes it’s a specific person. As I read, I wondered if you weren’t writing to your father. Not for him, but to him.

Safiya Sinclair: I didn’t know whether he was ever going to read it, so I didn't write it to be read by him. I hoped that he would and that he would understand me more. If there was any reader I thought about when writing the book, it was my younger self, that teenage girl who first picked up a notebook and found hope in words, found poetry to be a space of wonder that could transform pain into something beautiful. Without her determination, I wouldn't be here. So, the book is a tribute to her, and any young girl who like her feels that desperate sense of unbelonging and wants to forge for themselves the woman they want to become and the life they're going to have. I wrote for her.

Ladane Nasseri: Writing a book is an ambitious project with so many questions and so much unknown as we begin. What is the one thing that was clear to you from the start?

Safiya Sinclair: I knew that I was always going to write about the power of poetry to change a life. I wanted this to be a very strong takeaway from the book because it is so true to my life. When I talk about poetry as survival, I say it because it’s what saved me. So, that was one of the guiding lights. I also knew that I wanted the prose to read a certain kind of way, very lyrically, very poetically, I wanted the prose to be lush and reflect a Jamaican poetic. That was very important to me, that the language reflects the landscape and the culture and the music and the magics of my homeland.